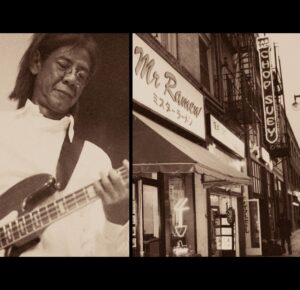

MR. RAMEN · SHINOBU-SAN · TRIBUTE

- March 29, 2021

- 9:37 pm

- danconia

It’s hard to adequately explain the magic of having lived in Little Tokyo (Los Angeles) during its recent rebirth—which has sadly ended.

It was like stepping into a portrait of an old Japan that history had already erased. A land that time forgot—the fifth chapter of 1Q84.

The men and women who inhabited the Little Tokyo of my lucid Ninkyo dream were relatively new immigrants, having arrived from Japan over the past fifty years—and they mashed in with the preexisting often elderly Issei and Nisei (plus a new generation of Japanese Americans).

These immigrants were mostly untouched by the cultural changes that took place in Japan during this period. And as such, much more closely resembled the people that I had expected to find on my numerous trips to “real” Japan but never did.

So, the books, anime and movies had not lied to me. Takakura Ken and Fuji Junko still walked the earth. And in fact, at that moment in time—they did.

This community of Little Tokyoites that I had injected myself into was filled with folks who spoke Japanese as a first language and carried on the aesthetic, creative, ethical and cultural traditions of their homeland.

This all worked out perfectly for me as I was after getting inspired by, immersed in and educated by that same Showa Era period that merged American and European with Japanese culture, which in turn produced a truly groundbreaking heroic, idealistic retro-futurist artistic sensibility in creatives like Tadanori Yokoo and Yukio Mishima.

As my art career grew during this period living within the community, I became familiar with many of the local flavor folks (pun intended) who not only were the lifeblood of Little Tokyo but also were literally producing the foods, booze and fun that went into my own (blood).

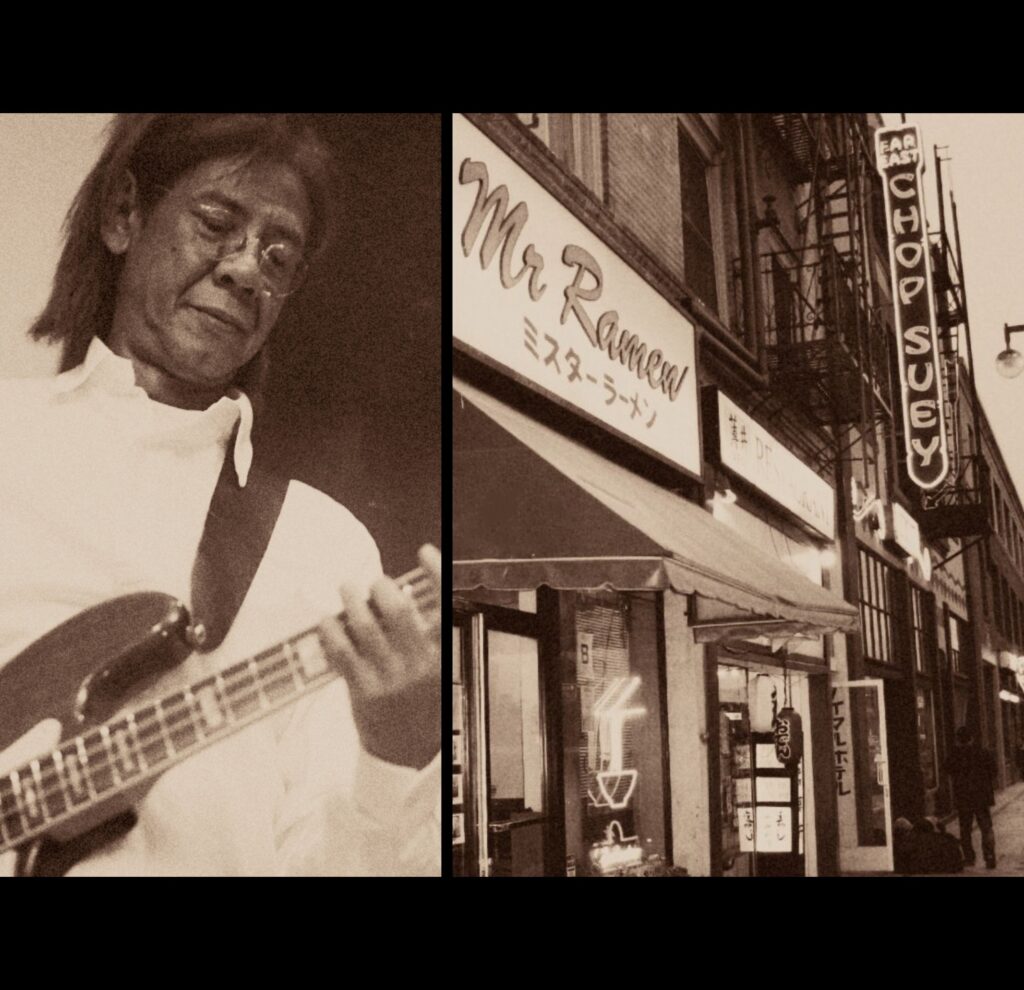

One such man was Shinobu Sakuma—aka, MR. RAMEN—the head chef, shokunin extraordinaire and local celebrity at the famous Little Tokyo Ramen-ya bearing the same name.

Shinobu-san arguably had the best ramen broth anywhere in North America—and like Johnny Cash—I’ve been everywhere, so I can say it. And yes—I have had all the “artisanal”, “artisan”, “craft” “yummylicious”, “traditional” and “authentic” Yelp Elite and EATER choices—served up via (repetitive not-so) smart marketing over the years.

None held a candle to Shinobu-san’s talent and his adherence to Japanese culinary standards—which produced some awesome bloody Ramen in the Tampopo tradition.

But that’s not how or why I ended up creating a massive 40 foot mural for MR. RAMEN’s wall.

That happened as a result of my friendship with Shinobu-san, which emerged out of the years (and years) of partying in Little Tokyo’s safe, amusing and eccentric nightlife scene.

Shinobu-san was extremely friendly, (very) generous and engaging. I had many great conversations and laughs with him—even though it was a mix of Japanese and English (with help from the bar patrons), we were able to connect as it regarded our mutual affinity for many of the same elements of Japanese culture, which I was in Little Tokyo to learn about and promote.

In addition, over these years he somehow figured out that I was mildly frustrated by the fact that Little Tokyo’s various community organizations were not quite as fond of some of my pro-Japanese art, as many of those icons and iconography had become politically incorrect. In fact, there were many micro-controversies in Little Tokyo about the eccentric weirdo artist named Sean.

And on so on that occasion when he asked me to make a mural for the wall of Mr. Ramen, which was of course my honor to create—he was clear—I did not have to self-censor. He told me that I could create whatever the hell I liked. As one would expect from a great Artist—Shinobu-san understood the heart…of an Artist. And luckily, what I liked was he liked—that 50s-70s Japanese pop-culture vibe, full throttle—which he had grown up with. Aspirational, inspirational Showa-era iconography.

Theater of Life: Shinobu-San’s Memory Lane” was what I titled the piece. It covered many years of culture, popular culture and included my own creations and creations of others whom I admired. I built the entire mural as a set of Japanese screens, where one could peer into various universes and lose oneself within them. The center of that world was Ayako Wakao—one of leading ladies of yakuza (and normal) Japanese cinema—also one of the most beautiful women that I have ever seen.

The art itself is sort of like a Ralph Bakshi “Cool World” multiverse. A place where all these characters and icons live and play together. Or rather, the kawaii ones are the adverts and the naturalistic characters are the heroes and villains.

The name of the art “Theater of Life” comes from the Japanese novel and film series starring Tsuruta Koji of the same name (which I recommend).

The overall energy and concept itself is a celebration of that odd reverse pop-multi-cultural engineering that took place in Japan from MacArthur’s era until the early 80s—a walk down memory lane for Shinobu-san (and me too!). A Japanese lens on the West and back again and back again. Much like how Murakami writes his novels—in English and then translated to Japanese and then translated by another person back to English. Makes sense? Not really?

All culture is a conversation—like the Hanafuda cards, introduced by the Portuguese traders, which laid the groundwork for Nintendo and all sorts of interesting games—mashed together with the infamous Chinese novel—All Men are Brothers (Outlaws of the Marsh), which combined with that same gaming universe, via Ukiyo-E and so much more—resulting in the giant dragon tattooed on my back on upon the soul of men like Shinobu-san.

The thru line—the common thread—is and always will be…the idealistic spirit of MAN as HERO—made real by the men and women of Japanese culture, and our own, represented by the artistic creations of those who want to see life as it could, should and ought to be—whether their medium is paint or broth.

Coming Soon: A non-exhaustive live of some of the characters and visuals contained within the art.

POP·TAG

danconia

ULTRAMOD MAG

Your premiere resource for contemporary and classic ART of the UltraMod persuasion plus all the new news, re-reviews and pop-cult that’s fit to print, from your most MOD-est tomodachi at Pop Art Land (Hollywood, California), ENJIN Factory & The D Gallery, located in dynamical Downtown Dallas, Texas. ٩(^ᴗ^)۶

TIME MACHINE

INSTA LINKS

Sign up for our Newsletter

We will never sell your info nor send over junk—only the very best information will we serve :)